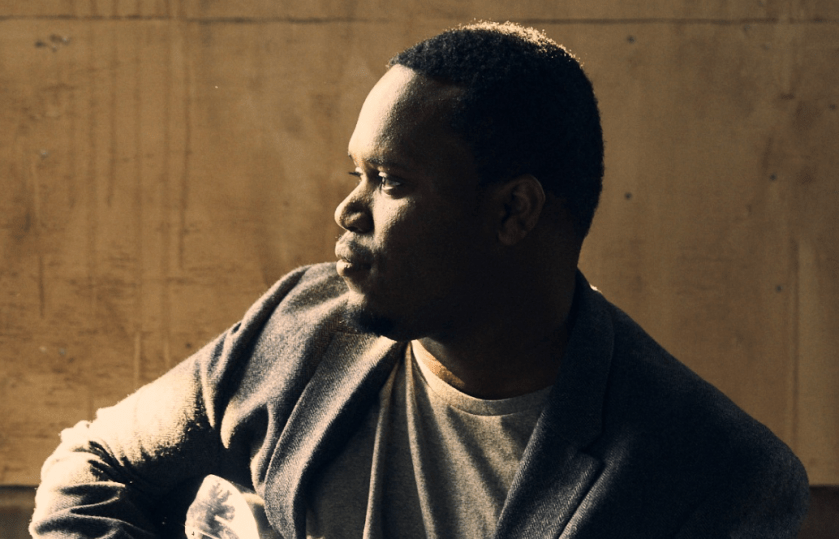

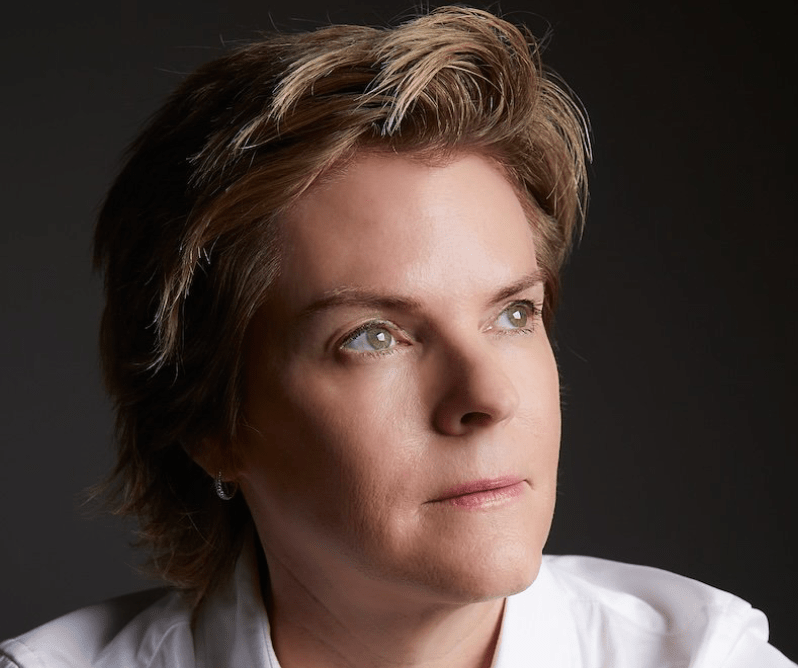

Sweet soulful sounds and relatable, empowering lyrics are the unifying theme on Kelley Mickwee’s Everything Beautiful, which otherwise captures a number of moods and stages of life.

Mickwee didn’t write songs for this record so much as she assembled them from her catalogue. She wrote some songs a long time ago and only one specifically for Everything Beautiful: Force of Nature. It was, like few other soul tracks before it, inspired by an episode of the NPR show StarDate.

“The beauty of life is the movement of change/It don’t ever stay the same/Light takes time to travel/Making its way through all that matter,” Mickwee sings.

“I don’t think I got it right, which is good because that would be plagiarism,” Mickwee joked. “I remembered pieces of what he said and put it together to fit what my point was.”

Her beliefs veer all over the place, jumping from scientific fact to religion to nurture. It’s a good reflection of where Mickwee is spiritually. She’s a bit all over the place and doesn’t pretend to know the answers, but finds use in positive practices.

“It’s all a wonder to me,” Mickwee said. “I feel very connected to astrology and Native American culture. I do a lot of grounding. Just straight up feet on the Earth. I’m not a Christian. I investigate different avenues.”

“Force of Nature” isn’t alone in being joyful; “Joyful” is quite literally the name of the first song on the album. “About Time” is an inspirational political sermon. And the title track is a sublime nature walk and the rare song of remembrance that avoids focusing on the pain. When the emotions hit, it’s hard to tell whether they’re hurting or healing you. There’s plenty of other moods on this album, but none so frequently drawn on as joy.

“Comes Out Wrong” is one of the more unique tracks for Mickwee. It’s vulnerable and devoted in ways that few songs are. It’s a preemptive apology that’s genuine. It seeks to reassure loved ones that conflicts aren’t everything.

“It’s really hard to always remember how much I love them,” Mickwee admits, saying the song makes her think more of family members than a romantic relationship. “I was really humbled by an experience 9 or 10 years ago. Once you’re humbled, you learn the beautiful act of apology. I discovered how to be vulnerable and be accountable.”

Perhaps the discovery was too life-changing.

“I admit I’m wrong all the time now,” Mickwee half joked. “Probably too much.”

“You Lie” is a direct and somewhat fun takedown song, but “Long Goodbye” is a more satisfying breakup. The song presents the idea that trying to change someone is just a drawn out way of losing them. It’s something I’ve experienced from both sides but haven’t been able to put into such incisive words.

Of all the lyrics I’ve been delighted to hear put to soul music, it’s the self-examination and anxiety of “Verge of Tears.”

“You’re not the kind of man you think you are,” an artifact of gender left in from a male cowriter, is the harshest line the narrator hurls at himself, but the notion that everyone else can see his internal distress is the main fear of the song.

“The truth is no one can,” Mickwee says. “You think that your stuff is so important and other people are going to want to talk to you about it or pick up on it, but no one cares. They got their own stuff.”

It’s these specific scenarios that makes Mickwee’s writing so good. And while the songs may have been written at different times, they compliment each other so nicely with a consistent soft soul vibe. And whether Mickwee is uplifting, resolute, or pissed, she’s certainly empowering at each opportunity.

Above is the full episode as aired on WUSB’s Country Pocket, including both my interview with Kelley Mickwee and the songs we discussed, starting with Force of Nature, which turns StarTalk into inspiration. The interview begins with the second video in the playlist. You can hear the show live every Tuesday at 12pm on WUSB 90.1 FM or check the blog to watch it as a YouTube playlist. Visit http://www.WUSB.fm and http://www.kelleymickwee.com for more.